Curiosity is a state in which artists find themselves much of the time. The creative mind seeks out ideas to engage with almost daily. The spirit of enquiry in which this exhibition was begun is quite typical of this process and when the Markmakers group was invited to explore the ethnography collection at Warrington Museum, with a view to creating new work in response to the objects, a sense of anticipation and excitement was palpable.

The particular nature of the display at Warrington and its links to the earliest format of museums or Wunderkammers in Renaissance Europe, led the artists to explore the theme of cabinets of curiosity and they have spent many evenings in the galleries as well as visiting the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Oxford for inspiration.

From fake mermaids to willow patterned plates, the child mummy to gas masks, the strange mix of objects and oddities found in the galleries have resulted in the artists exploring ideas both personal to themselves and universal. Some works have retained a very direct relationship to those in the collection, others have evolved into wider considerations of modern day politics, how we address memory, and our labeling and appropriation of other cultures.

Markmakers hope that this exhibition will encourage you to explore your own ideas inspired by the artworks, and to revisit the museum’s collection with a renewed sense of wonder.

Louise Hesketh, Arts Development Officer, Halton Borough Council

Markmakers are Halton’s Contemporary Visual Arts Collective, meeting regularly at the Brindley Arts Centre and are supported by Halton’s Arts Development Team.

C of C. War.

Val. J.

May All Your Dreams Come True 1 & 2.

These pieces are inspired by the two large carved white magic figures from Sierre Leone which were evidently made as part of the white magic process to help the infertile chief figure to father children.

Piece 1 is a simple attempt to catalogue the pieces & define their purpose, using a copperplate style of writing common in museum display cards of the !9th Century.

Piece 2 is a fanciful attempt to explore the results if this magic process was an overwhelming success. The chief is given an extra 5 wives& 20 children, including 6 babies.

The work is produced through digitally generated machine stitch & the children are designed digitally by extrapolating their characteristics from the sketches of their parents.

The materials are transparent & semi-transparent manmade fabrics, overlaid and cut away.

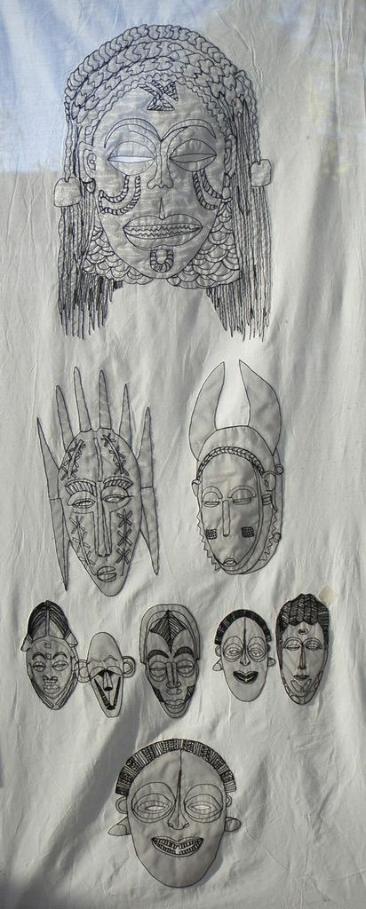

Here’s Looking at You.

This piece is inspired by carved masks represented in the Ethnography room. Further research has discovered a wealth of variety in mask making in 19th Century Central African States. The piece utilizes digital representations of 9 of them, developed into stitch.

The representations are produced in digitally generated machine stitch.

Transparent & semi-transparent manmade fabrics are used. The secondary fabric is applied under the stitch & then cut away leaving the relevant parts to show as silhouettes when the main piece is hung against the light.

The aim in this piece has been to present a clinical & scientific aspect rather than a personalized or emotional one, as is appropriate to a museum collection.

Janet Worrall

This work explores the notion of the Museum of the future, and the consideration of what is the most precious possession of the future visitors would be. Of which, in years to come, would, if not catalogued properly, be unidentifiable and leave the residue of something that was once a distant memory. My work is created through the notion of the socioeconomic influence of the media on contemporary society that has developed the tension of hyperrealism. The work contemplates the place of where the material ends and the nothingness begins and the ambiguity of the social intrinsic value of possessions where colour, form and materials are all equal. The pieces are made from materials that are reminisce of something familiar through a feeling of knowing or an intrinsic deep understanding of what the work is trying to say.

Susan Meyerhoff Sharple

HYBRID series

Created during the 21st century, the age when: science is developing at an incredible pace, genetics are being modified for a more productive food source and breeds are being crossed at a whim for designer pets, this body of work has allowed Susan Meyerhoff Sharples to reflect, and to focus on preoccupations of evolutionary processes which have been inherent in her work for a long time.

She has produced this new series in response to the Ethnology collection of the museum, inspiration drawn from mythological beings of part man, part creature that appear in the folklore of many cultures world-wide.

More specifically these were found in Egyptian tomb drawings and funeral figures depicting deities such as: Horus,Thoth, Sekhmet, Bastet.

Mermaids from Japan also influenced her work, contrived skeletal forms, curiosities intended to deceive the Victorians at a time when the Darwinian theories regarding the origin of the species were new and controversial.

Viewed from a playful perspective, she explores the possibilities of the evolution of such cross-breeds and mutations in a three dimensional form.

Her sculptures have been realised through copper fabrication, metal casting and silver electro-plating.

Tony

On my initial visit to the Museum, my attention was drawn to the Masks in the cabinets. I happened to wander round the corner and discovered the World War 2 exhibits and this immediately struck a chord in my psyche. I was born in the latter part of the war on the outskirts of London. I was frequently told that during air raids I refused to be put in the large gasmask designed for young children. This is where I made the link between the masks I had seen and the Twentieth century equivalent, the Gas mask.

The two World Wars seem like museum exhibits and ancient history to my grandchildren. My three dimensional, grey box piece has lino prints of figures in gasmasks printed on old, brown wrapping paper and placed in bottles reminiscent of those used for specimens in museums.

The box is decorated with two dimensional marks of clouds and bombers and painted a dull, wartime grey. Above the box is a mixed media interpretation of a plotting chart for enemy aircraft recognition.

Judith Ferns

Baskets seem to have taken over my creative time recently, studying, collecting and making them. Basketmaking is one of the oldest crafts but because the materials used are perishable they don't survive. Many museums have baskets in their collections, this means that appropriate methods of conservation and preservation are possible and that the baskets may be exhibited or seen by appointment. I don't make functional baskets and my recent work was on a large scale, baskets made using woven paper and with hidden text. My latest baskets are tiny and created for the sheer joy of manipulating the material available from my garden, a grass of the Carex family, starting as a copper colour but fading with time.

Each basket takes shape depending on the number of stalks which are bundled together and coiled using waxed linen thread, some have seed heads hidden inside, some have hidden spaces for secrets.

Allison John

Different and yet essentially the same?

Through exploring the artefacts in this Museum, we appreciate how different the world is that we live in today, from the world experienced by those people represented here. How priorities and values have changed. How the way we use our world has changed. How different our lives are compared to those people 'seen' here through their objects.

Although these changes may or may not always be for the better, the world we live in is essentially the same place with its beauty and complexity, and the transient nature of life makes it important to stop and appreciate this.

These images are worked using pages from a Bible found discarded in the back room of a second hand book shop, and no longer used. They represent both the loss of spirituality in our society, and highlight our changing way of life, as we see the written word being superseded by the electronic one. They are hung unframed, vulnerable and exposed, just as we can be in our stressful modern lives.

The images are based on different aspects of our world. A changed world culturally from the one seen through the objects in this Museum, but essentially with the same physical beauty and complexity now as then. They allow us to reflect on this, and consider how like these artefacts, we can preserve this for the following generations.

Sue Archer

Why are everyday objects displayed in museums? Does placing them in a museum setting give them some enhanced importance? Mundane objects are now viewed as things of beauty.

With this in mind I looked at the Japanese textiles in the museum, in particular the Samurai outfit, which incidentally derives its strength from layers.

This led me to explore Japanese textiles on the internet and I came across BORO – patched, worn Japanese garments which have become objects of beauty.

I thought the philosophy of recycling, reusing and repairing over generations fit into my way of working i.e. trying to take something old or unused and create something of beauty where the most valuable part of the object is the time spent creating it.

As it is the patches and the colour blue that are predominant in BORO garments I decided to concentrate on them and by placing them in a museum setting perhaps imbue them with some enhanced importance.

Amanda Oliphant

A Juxtaposition of artistic objects - Artist Box l and ll

“For in my opinion, the most ordinary things, the most common and familiar, if we could see them in their true light, would turn out to be the grandest miracles of nature and the most marvelous examples, especially as regards the subject of the action of men”.

Michael de Montaigne – On Experience

The product of creating…Artist Box l was discovered in Austria in 2008 by chance in an antique shop and is full of utilitarian artistic assemblage. It consists of nearly all its original items and its original date is unknown. Artist Box ll kindly donated by an elderly lady of 93 years and is filled with treasured objects from around the world, collectively preserved. There is an associated thread between person and the spiritual journey of each object. These artist boxes uncover secret souls of the inanimate; they gave the artist greater freedom and visually describe the wonders of creativity.

Rachel James

Agonisingly beautiful.

A response to miniature Chinese shoes for bound feet.

One theory to explain the binding of feet was that smaller female feet made them more desirable for marriage. Another, that foot binding raised the status of women so that they would not have to work in the fields. To be able to leave such a “small” footstep, to force feet into unnatural shapes, became the price of acceptance and approval.

These shoe forms you see are unrealistic to wear, painful to look at, and displayed in shoe boxes that themselves show the signs of status. A warped image of beauty binds not only feet but the spirit.

Angela Sidwell

“Bound”

During my visits to the Warrington Museum Collection I became drawn back again and again to the mummified boy and animals, a weird sense of knowing that beneath the many layers had been life, remnants of this forever unseen beneath the fabric.

I had the same feeling when I saw the casts of the entombed figures and animals at Pompeii, their last fleeting moments of life – you could almost touch it ... you were there.

I created “Bound” to feel closer to the boy himself, to see him – reflections of a life that was.

He is holding a bird – an offering to the Gods? a beloved pet to keep him company in the afterlife? There is no doubt that the Egyptians had very strong emotional and spiritual connections to the animals around them.

Exploring the relationships between humans and animals has always been foremost in my work and exploring our reliance, of them, in its many forms.

Sharon Lelonek

“Layers of Time and New Beginning`s” 2014

Walking into the Gallery Space Cabinets of Curiosity, I was Like a Child in a sweet shop. I was struck by all the different kinds of materials used to create objects; objects of religious and historical relics symbolic from our ancestry past. Today these relics have been carefully preserved, what I would like to do is touch and feel the remains of the materials, but I have to visually see "something left behind" and listen to the stories unfold and conjure up my own thoughts and imagination of what I see in front of me.

Reflecting upon the stories and visualizing on how our ancestry’s environment would have been and the materials available for them to use. I have taken these thoughts into consideration whilst creating my own piece of art work; from the materials I have used, from where they have originally come from and how I can create different effects from using the same materials creating something new. The sculpture you see in front of you today has been created out of old garage doors, creating layer`s and each layer created represents layer’s of reflection and layers of time. We as human beings, on our journey of life, we absorb so much information and we have to change and adapt ourselves each time we make decisions and with every new circumstance that comes our way. I have created this sculpture to represent the past, creating layers of time and forming new beginnings.

Maria Tarn

Framed textile piece entitled ‘Onward and Upward’

My starting point was the Chinese ceramics in the cabinets; capturing the everyday alongside the ceremonial. I was particularly interested in the flower and bird decorations on the vases. This focus became an integral part of the designs for the birds in my work. The patterns are repeated then reproduced in machine embroidery on dissolvable fabric.

During my research I read the Willow Pattern story which has featured on everyday ceramics for generations in England too. The two people in the story are immortalised as lovebirds eternally destined to fly in the sky. They are trapped inside the bodies of birds, caught in a certain time and place.

I immediately saw a connection between them and the artefacts within the museum which are also trapped in a certain time and place.

The birds are destined to be constantly moving in a restless dance onward, forward and upward, consequently never static. I saw parallels between this image and how it reflected the current changes in the museum and the new developments.

However much we try to capture time through images, objects and stories or in museums nothing stands still for ever.

Niki Carlin

Remnant

Wet Plate photographs on glass

When I was a child the highlight of any museum visit was the ‘dead stuff’, I was drawn to the remnants of things that were once alive and found beauty in the traces that were left behind. From Egyptian mummies and fossilised remains to draws of insects, carefully pinned into their glass-covered mausoleums, the fascination has stayed with me. For this project I have drawn on my own small collection of ‘dead things’ and tried to convey the beauty that I see to a wider audience.

For me, the things that were once alive or held life do not lose their sway once that life has departed, the stillness of death gives us the opportunity to look a little closer at the intricate and delicate structures that allow the gift of life to flourish in the first place. The vestiges of life are all around us, yet are so often overlooked or discarded that many fail to stop and see the beauty that I find in such things.

Cary Hughes

From initial studies at Warrington museum, I was drawn to the uncanny Fijian mermaids with their mummified scorched skins and the interesting story that in fact they were not mermaids at all.

My work has explored the mix of joining and disassembling, working with dolls that had been used, cast aside, and abandoned.

Crochet and drawing pulls the work together with a need to narrate in the visual a story of rejection, of loss, of the uncanny, a story that is not a singular incident in one’s own history but is also passed down the generations by unseen insecurities that manifest in adult neurosis.

Life in my opinion is not the spangled coloured, utopian happy ever after, that the mass media is spoon feeding every new generation; we are all on a conveyor belt going nowhere, but back to the doctor for Prozac, before returning to the new national babysitter, social media.

“The uncanny is a crisis of the proper: not simply an experience of strangeness or alienation. More specifically, it is a peculiar commingling of the familiar and unfamiliar”. (Royle, 2003)

Casey Carlin

Vita et Mors (Of Life and Death)

As a society and in western culture we have sanitised the process of dying and hidden the rituals of death. Not openly spoken of, the subject is now taboo, hidden from sight but not from mind. As a Critical Care Nurse I faced death daily, never spoken of above a whisper, referred to through codes and euphemisms as though simply saying the word was unclean, something to be left in the shadows where it belonged. Having witness so many leave this life to whatever lays beyond it was immediately apparent that death is as special as birth but we have lost our ability to cope with such things.

The cabinet of curiosities has allowed me to engage the subject and bring it forward for consideration. The images and artefacts created are inspired by the Victorian Mourning Broaches that were worn as a sign of remembrance. With death being a part of everyday life during the era, the use of wet plate collodion has allowed me to present ghostly images in the guise of their Victorian counter parts. My aim is simply to raise interest and awareness in how distant we have become from one of the most natural and inevitable aspects of life, to raise the question; should it be hidden?

Jeni McConnell, 2014

The Value of Nature

Arthur Crosfield donated over one hundred items to the Museum in 1895 and amongst his collection was a ‘fly whisk’. As I researched around this object and its donator I became intrigued by the stories which unfolded; I wanted to create my own fly whisk, with a twist.

The Crosfield family were soap and candle manufacturers; today the Unilever name continues the soap-based manufacturing tradition in the town on the same Bank Quay site. Warrington Museum, one of the first public museums opened in 1848. Crosfield was well aware of it, and its growing collection.

Whether it was the intrigue of soap making raw material sources, or the growing museum collection of donated objects from far off places that hooked Arthur to venture abroad, he travelled extensively and bought many treasures including the collection of objects from Upper Egypt which he eventually donated to the museum.

They still provoke questions today; some objects are genuine but others are fake, tourist items sold to the unsuspecting visitor who perhaps knows no better.

I was intrigued by the simplicity of the fly whisk; it couldn’t be anything but a genuine item used to keep flies away from humans, but how does that translate to our lives today?

My fly whisk is constructed of re-appropriated materials, shifted from their original purpose to be something else. Perhaps the viewer suspects this, or maybe they believe my materials and my object to be genuine.

The text printed onto the beeswax soaked brown paper is a Natural England report into the importance of protecting nature in our world today. A fly is generally a nuisance, an unwanted pest, yet they also have a beauty and a purpose in our environmental cycle; do we welcome them, or should we rid ourselves of them?

Crosfield was obviously a well travelled man and passionate about his fellow humans. He must have had a creative inquiring mind; he was intrigued by our past and caring about our future. His first published small book of poetry here gives hint to his well travelled knowledge of European places and people. Its purpose to voice his concerns about the impending affects of the First World War.

With all his attributes I wonder if he would have been hoodwinked by my fly whisk. How would he have reacted to the questions we all face today about our environmental impact, as we continue to rid ourselves of things we consider to be undesirable.

Cathy Rounthwaite

The jostling artefacts in the ethnological gallery record a culture far removed from our own, everyday items, relics and treasured objects give an insight into different lives. Responding to the collection, I was drawn to the Inuit jawbone – a chronicle of hunting which captures the imagination with strange creatures, brave hunters and village life. The images scratched into the surface, then stained, have a quality of line reminiscent of a monotone print etching.

This links into my recent work which concerns folklore, tradition and narrative, and with a textile background, I currently work in 3D, print and book forms.

I have taken elements of the scrimshaw hunting record to create a narrative. Taking it into a contemporary form, scratching the black ink into paper to create a book, I have then taken my narrative back into bone. I have also taken the narrative images into print, experimenting with mono prints to explore shape and line, to describe the environment and capture the activity and skill of the Inuit hunters.

Jennifer Kenworthy

Votive Offering – an object/gift displayed for religious purposes in order to gain favour with supernatural forces.

Inspired by traditional votive offerings I have created a collection of my own personal votives. I was particularly fascinated by those offerings which depicted faces and their pattern-like marks used to capture their detail and expression. No, one face or person is depicted within my offerings but their use of pattern and line evokes personal memories of my own mum, who sadly passed away 8 years ago. These votives are offered as a precious reflection to a life which cannot be replaced. Each 2-dimensional piece has been purposely created on a miniature scale. The scale of this piece is not only intended to create intrigue for the viewer but also reflect the fragility and sensitivity of the subject matter.

Cliff Richards

Maori facial mask

I was taken by how many representations of faces and masks were in the collection. I was particularly intrigued by the Maori tattooed facial cast.

The facial marking conveyed a meaning to the wearer and to his viewers. Powerful men had individual designs which expressed importance . The facial marking elevated the man, increased his pride, his power and his attraction. Both his fearful fierceness and his manly attractiveness were enhanced.

Women were excluded from this ritual.

Slaves were excluded from this ritual.

I was drawn to and fascinated by the beauty of the Maori face. The notion of transformational change occurring by scarring and chiselling a surface. Thus a being could be permanently transfigured.

The obsolete chicken brick was received from disposal and transformed from an object with no purpose or future to and object of power and ritual by the same process.

mages of our most powerful have been enhanced by facial marking. Masks are available for you temporarily become transformed, to become powerful and attractive.

Jane Copeman

OLD QURNA EGYPT

The Egyptian collection here in Warrington Museum mostly comes from excavations in Tel el Armana. They are almost identical to many of the artefacts found in the Valley of the Kings on the West Bank of the Nile, opposite modern day Luxor, ancient Thebes.

Qurna (pronounced el Gurna) is the name of the ribbon of villages that encircled the Theban necropolis.

The Egyptian workers of Qurna have worked for generations, and still work today, on excavating the tombs of the Pharaohs. They have lived here in an historical and closely knit community. Gradually, in the name of progress, mud brick homes, intermingling with some of the tombs have been destroyed. Families have been driven out and rehoused in concrete blocks far from their places of work. There is scant possibility of keeping donkeys and livestock or growing crops. The remains of the old settlements are dust, rubble and tattered remnants. All this in the interest of making the approach to the tombs more attractive to the tourists.

The prints exhibited here come from a number photographs I took on the West Bank over a number of years and reflect the sadness I feel for the people of Gurna.

Jacqui Chapman

Mummy, Boy

This painting was inspired by the Mummy of the child from ancient Egypt, around 300 BC.

What I found reverent was the fact that this was a real boy, same age as my youngest child, 14, and it was moving to read the gallery information about respect for the exhibit as a real person. It is small and fragile, perfect in its stillness and was once loved.

The x-rays done in the 1980’s inspired this work. I chose to paint his feet that will never walk in this world again. It is sad, quiet and spiritually very potent.

I painted over a painting from before as this too has a hidden past which is suggested by the lumpy texture in places.

Jane Chinea

Drawing on two themes from the ethnological room; The history of deception and ‘passing off’ as real specimens, hoax fabrications of mythical creatures, which subsequently have earned their places in museums as artefacts in their own right; (for example the Fiji Mermaid on display here at Warrington); and Integrating this with Egyptian beliefs, myths and rituals Jane has created her own ‘authentic’ museum exhibits. These tangible creatures are vested with Egyptian mythical powers, which are represented using the Egyptians own colour symbolism, helping to add authenticity, majesty and create a deeper more potent meaning.

Using the same taxonomy structures employed by museums to order and catalogue their collections, Jane plays with and questions the reality of the Mythological, Egyptian Goddess Isis’ seven scorpions, and their purpose, which was to protect her from her enemies. Bringing these formidable creatures into reality as actual, authentic artefacts; unquestionable, found, preserved, and taxonomized in true Museum style.